|

|

|

Visions from the Golden

Land:

|

Burma's long political isolation has ensured that its rich traditions of art and culture have been little known outside Southeast Asia. Although it occupies the largest mainland area in southeast Asia, Burma’s political isolation has ensured that its contacts with the rest of the world have been much reduced since it became independent from Britain in 1948. Featuring a magnificent new gift to the Museum, the Isaacs Collection, as well as specially commissioned contemporary works and loans from around the UK, this major exhibition will examine the extraordinary tradition of lacquer production in Burma. Because of past links between the two countries, British collections are rich in Burmese materials. Highlights include manuscripts from the British Library, and from the V&A a nine-feet-high Buddhist shrine - a monument to the skills of Burmese woodcarvers and lacquerers. A video made in the workshops at Pagan demonstrates that lacquer is still very much a living art. Lacquer is still used for an astonishing range of purposes by the many different ethnic groups of Burma and its varied social and cultural role allows a whole range of subjects to be examined - Buddhist rituals, sculpture, manuscripts, architecture, theatre, cooking and warfare of Burma from the 18th to the 20th century |

Exhibition Dates: 8 April - 13 August 2000 |

Despite being the largest country in Southeast Asia, Burma is one of the least-known. Its artistic traditions - and indeed the country itself - have been little studied. Bordered by India, Bangladesh, China, Laos and Thailand, it has one of the most diverse ethnic mixes in the world. |

|

In Burma, lacquer has traditionally been used for many purposes. This exhibition, inspired by the gift of the Isaacs Collection of Burmese lacquer, aims to use the art of lacquer as a means to explore Burmese culture, and, in a small way add to an understanding of this important country, known in ancient times as Suvannabhumi, the Golden Land. Lacquer vessels were produced in an extraordinary array of organic and tactile shapes, in cinnabar red, blazing gold and black. In the last two centuries perhaps the most common types were containers for carrying offerings to the monastery and the cylindrical boxes for the paraphernalia used in the preparation of the betel quid. This is a small leaf parcel containing tobacco, areca nut, spices, sugar and powdered lime, used as a digestive in Burma and other parts of southeast Asia. |

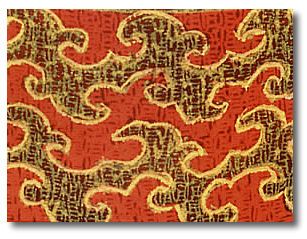

Detail from panel, early 19th century |

Box. 20th century, palm-nut, wood, coiled bamboo  Coiling split bamboo to make a vessel, lacquer workshop, Pagan. |

What is lacquer? Lacquer is tree sap (Gluta usitata) which sets as a flexible plastic, resistant to water, heat, and insect-damage. The tree is tapped by making deep V-shaped cuts through the bark, into which small bamboo cups are wedged to collect the straw-coloured sap. After collection the sap quickly turns black but remains fluid and is stored in jars for distribution. It can be applied to a wide variety of surfaces such as wood, leather, metal and palm-leaf, but is most often used on vessels made of coiled or woven split bamboo. The liquid sap can be used as varnish, glue or ink, or mixed with ash or sawdust to make thayo putty which can be sculpted. It is not known when lacquer was first used in Burma, though it is thought that plain lacquered wares were used, and probably made there from the 13th century AD onwards. For many centuries the best quality lacquer has been collected from the Shan States in eastern Burma. Lacquer is a natural plastic and sets to form a surface resistant to water, heat and insect-damage. It can be used on a wide variety of surfaces, such as metal, leather and palm-leaf, but, above all, on split-bamboo basketry. As well as being used in its liquid form to coat and decorate vessels, the sap can be mixed with ash or sawdust to create a putty (thayo), which can be moulded or sculpted. Decorative techniques such as yun and shwe zawa, were gradually introduced later, probably as a consequence of warfare with Thailand and the capture of lacquer craftsmen already proficient in these techniques. The yun pattern known as zin me, after the Thai city of Chiangmai, is an example of the Thai stylistic influence. Although not the oldest piece of Burmese lacquer work, the letter cannister in Case 5 is one of the earliest dated pieces. It originally contained a prize certificate (displayed on the wall) which dates it to 1902. Lacquer vessels are made by hand, using many methods recorded 170 years ago. They can undergo up to 26 different processes during production and it can take 3-4 months to complete a single small vessel. Lacquer vessels are not solid lacquer, but have a wood, bamboo or horsehair base, coated with many layers of thayo and liquid lacquer, polished to create their characteristic smooth surface. |

Types of lacquer vessels |

||

Mid-20th century, lacquered bamboo basketry; a betal box decorated with the symbols of the zodiac. |

Top of a betel box with engraved decoration. |

|

| Many everyday objects are lacquered such as cups, bowls, trays, and plates. However, some vessels, seen throughout the exhibition, are specific to Burma. kun it Boxes used to hold the requisites of the betel user. An upper tray holds cups with the ingredients for chewing, a small metal lime box, and nut cutter. A lower tray holds tobacco leaves. Below this are fresh betel leaves. The box has a tight-fitting lid protecting the interior, preventing the betel leaf from drying out. Every home would once have had a betel box. |

||

Decoration |

|

Hsun ok from Mandalay, late 19th century |

Offering vessel from Shan State, made of lacquered basketry. |

yun (also the Burmese for 'lacquer') is the most common lacquer decoration. Designs are made of thousands of tiny lines engraved on the lacquer surface and filled with coloured lacquer. The engraving for each colour has to be done separately, with a lengthy period of drying in between. hmanzi shwe cha uses moulded and sculpted thayo to create relief decoration. Sometimes the pattern is built up using thin strands of thayo, but to create a repeating pattern the thayo may first be pressed into a mould. The whole item is then covered in gold leaf and inset with coloured glass. shwe zawa produces designs of gold on black. The background and outline of the design are painted onto the lacquered surface with a gum mixture which prevents gold leaf from sticking to the object. The design is then covered, first with colourless lacquer and then gold leaf. Before the lacquer has set, the object is washed. Where the gold leaf lay on the gum it washes off and the black surface shows through; where it lay on lacquer it remains. Gold leaf was also used to decorate dry-lacquer and wood sculpture. |

|

Designs |

||

Za Yun pattern decoration of a betal box. |

|

|

| The exhibition displays various yun designs - the planets of the days of the week, the signs of the zodiac, and motifs such as 'Chinese cloud-collar', gwin shet, and pabwa. There are also examples of yun decoration depicting scenes from the Ramayana and Jataka Tales. Though Indian in origin, the Ramayana, the epic story of Rama and the search for his captured wife Sita, became inceasingly popular in Burma during the 19th and 20th centuries. The Jataka Tales are a series of stories about the former lives of the Buddha. Each Tale emphasises a moral value demonstrated by the Buddha-to-be. |

||

|

Buddhism in Burma A Burmese proverb states that 'To be Burmese is to be a Buddhist'. Buddhism reached Burma from southern India by the 5th century AD, and despite Christian missionary activity, Buddhism remains the embodiment of Burmese cultural identity. The school of Buddhism practised in Burma, Theravada, is practised in most of Southeast Asia and in Sri Lanka, and it lays great emphasis on monastic life. Most young men in Burma, even today, spend a short time as a monastic novice and some also return to the monastery in old age. <==Shrine from the palace at Mandalay. 19th century, gilded and lacquered wood. A Buddha image on a tall throne surrounded by vessels, adoring disciples and a manuscript box (Case 16). Victoria and Albert Museum |

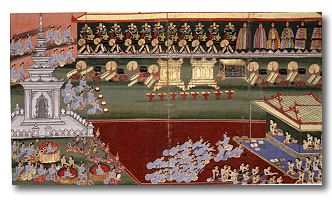

Parabaik illustrating royal gifts to monks, including many offering vessels, 1857 (Case 18). British Library |

|

| The ritual of donation Through making offerings, lay Buddhists gain merit. The ritual of giving in Burma requires both receptacles for offerings (hsun ok, kalat, alms bowls), and donations (Buddha images, rice bowls, funeral salvers and manuscripts), all of which were made using lacquer. Many surviving Burmese manuscripts are of Buddhist texts and follow the Indian tradition in shape, material (rectangular palm-leaves) and protective covering (decorated wooden covers). Most were inscribed with a stylus and rubbed with lamp black to show the text. However written text was possible using lacquer ink. Manuscripts were kept in protective chests. In Case 22 is a recently conserved panel from one of these chests, decorated with scenes from the Mahosadha Jataka. (Top) Parabaik, made of stiffened paper, were mainly used for illustration with a small section at the base reserved for text. The opened parabaik in Case 18 shows royal donations of lacquer vessels to monks, like those displayed alongside it. |

Secular use  Betel box tray with yun design of Rama on horseback The protective and decorative properties of lacquer mean that the opportunities for its use are almost limitless. In the average Burmese household, lacquered basketry was used for making vessels for the storage, preparation and consumption of rice such as storage pails, steamers, serving trays, food stands, and cooked rice carriers. Lacquered vessels were also used for other foodstuffs, including liquids. The main meal may have been accompanied with water served from a carafe, preceded by snacks served from a lahpet (pickled tea) tray, and followed by a digestive from the betel box. In most Burmese houses, substantial furniture did not exist, but clothing was often kept in a special cylindrical basket (bi it) and medicine also had its own containers. When theatre and music troupes visited, they brought their own lacquered objects - masks, costume, headdresses, and musical instruments. Betel-chewing has been enjoyed in South and Southeast Asia for many centuries. A quid made of areca palm nut wrapped with slaked lime inside a leaf of the betel pepper vine is stowed in the side of the mouth and squeezed now and then between the teeth. Betel was synonymous in Burma with goodwill, hospitality, geniality and social enjoyment, and everyone owned a betel-box. Men, women and monks of all ages and ranks chewed betel. It was embedded in social convention and court ceremony, and betel quids were a token of favour in village courtship and royal courts. |

|

| Sunrise over the Irrawaddy River Photograph courtesy of Maurice Joseph FRGS ARPS and Norma Joseph FRGS FRSGS |

Exhibition Dates: 8 April - 13 August 2000 A fully illustrated catalogue, Visions from the Golden Land: Burma and the Art of Lacquer, by Ralph Isaacs and T. Richard Blurton, will be available from the Museum bookshops. Price £24.99 (softback) and £40 (cased). The exhibition’s education and outreach programme is supported by the Burma Project Open Society Institute), the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and the Charles Wallace (Burma) Trust. For full details of events, educational bookings and other resources, please contact ‘Burmese Lacquer’, Education Department, British Museum, London WC1B 3DG Telephone 020-7323 8511/8854 |

References 2. Official Exhibition Leaflet 3. Materials provided by the the British Museum Officials. |

21st June 2000 |

Tell A Friend About This Site! |

|

|

||||||||