| Forest Sangha Newsletter | July 1995 |

|

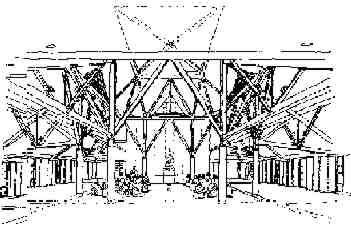

Conducting the Orchestra of Form [Tom] The reason for the form emerging as it has is based on notions I discussed with Ajahn Sumedho; one of which was that the laity and Sangha should somehow have a more convivial raltionship inside the building than has been the case in general. The gatherings would generally be quite small in numbers, and in the case of the larger gatherings, the question was how to accomplish that same intimacy without a very long nave for the laity which is usually empty, as in a cathedral. How do you have a building that is always quietly occupied even though you may have very few people in it? And when you have a lot of people it doesn't feel overwhelming? The square seemed to be the very best form for that; not only was it an implicitly interesting form, but also because you can raise roofs on it quite easily, as well as reflecting the square of the Sima area. The supporting structure itself from the earliest days had been a circle which, for reasons of structure and material, developed into an octagon.

Your very first drawings for a temple of some sort were in 1984?

It's still that stupa shape isn't it? |

|

... another thing that came out of the oak structure was the idea of the forest. |

|

The overwhelming idea that Ajahn Sumedho wanted was this meditation space. Clearly there is no 'perfect meditation space', that is impossible to achieve because meditation is a natural, personal experience and has really not much to do with the building. But there are certain things that are conducive to meditation - the atmosphere, the quietude and so on. He wanted a cave-like feeling, and that was where we really started four years ago. And we went on from there to develop the first design of the interior dome - the central form - which was at first a circle inside the square.

This was the dome inside the pyramid idea? When we started looking at the dome idea, the notion was to have the inner skin of the dome and then the outer skin of the pyramidal roof, which would be tiled. And there was a nice consonance because the sphere fits very well into the pyramid. But the only materials we could think of for the dome were either solid stone, concrete or plaster. When we started to think about how to make the plaster work, the acoustic report came through. This showed that the dome, which initially was about 40 foot in diameter, would be really bad for chanting. I really should have known that but I was so hung up on the perfection of the dome and the pyramid that frankly I didn't think of it. That kind of testing was gone through on many, many parts of the building. Not only through the choice of materials but also in the way we are putting them together. The main frame of the building is not an accurate material, green oak. (This will be cut from ecologically managed English forests). What we did was to make a trawl of different structural systems. First we looked at oak frame, but we could not make that work. This became transformed into a quasi oak-and-steel composite, which in engineering terms worked well, but in terms of simplicity of construction the idea became complicated. So at this point I had to intervene and design a new structure myself, going back to the eight columned octagonal structure. As soon as I had made a model of it I asked a carpentry firm for comment. And their comments were that they wanted to build this. They're very genuine people so I took it as a compliment. And the shape of this engineered structure in oak - did that vary from the dome shape? In my mind's eye it is still there. But of course it will be very difficult to read the dome unless you know it was once there. In retrospect, another thing that came out of the oak structure was the idea of the forest. I remember seeing the tudong monks in Thailand living in the forest with their mosquito net arrangement hanging from the branch of a tree. So the idea of the hall being like the forest I can see didn't really come out until the structure of the oak was there. The lower parts are like tree trunks which produce smaller columns, with little branches reaching to the upper levels. |

|

And what is green oak?

It is oak that has not been dried or naturally seasoned. If we used seasoned oak it would have been over twice as expensive. Green oak has a long history. Carpenters I have been talking to still understand how oak should be designed as a compression structure, i.e. all the joints are pushing downwards. The oak shrinks, but not in length. So we've chosen a material for a main structure which is imperfect, but we're using it in a way which understands that essential quality of change and plasticity. Evident cracks will emerge in the oak, and that's part of the process. So immediately we'll get a material which, after a few years, will look like its been there 100 years.

Following from that are the ideas for the floor. It was decided earlier that we'd use underfloor heating based on the experience at Harnham. We have a super-insulated building, and so the floor is an important element in terms of a radiant heat source. |

|

|

It won't be a brilliantly lit building. We will have side-windows and ventilation at the top of the central open space of the building, and we do that by having four dormers so the light in the 'cave' comes from above; the light from the side windows will be very minimal. Because they're so high above the floor level the changing light throughout the day will be very fine from there; that's the reason I wanted a white floor.

What other factors determine the colour of the stone and the kind of surface required?

You are looking forward to having what built by when? Foundations will be there by the end of July, then there will be a quiet period in August whilst the road is re-built by the highway authority. The oak frame goes up in September. Like all medieval buildings it will be pre-assembled in the workshop and brought to the site in bits, and then re-assembled to make sure it works. This will all take quite a time because it's a fairly big structure and we have to take very great care in the detailed work. It'll be about 4-5 weeks. This is the structure that carries the entire weight of the pyramid and must withstand the wind.

The structure is capped with a pinnacle which has also gone through a number of stages.

So Stage 1 is the completion of the main building and surrounding walls. And then later come the vestries and vestibule? It's always a balance between the materials you've got, what you actually do and of course the team that puts this together. The men on the site, the quality of their work and how committed they are to it. Right through the entire orchestra as I think of it. As though one is conducting a piece that has already been written and people have seen the score and they think, 'Aah this is wonderful,' but they've not heard the music. You can't hear the music until the building's built!

So what you're saying is that you couldn't really be expected to do that with any real sensitivity until you've got the building up and the interior is more or less finished in general? Perfection doesn't exist in art. All art is illusion, and architecture - that's an illusion too. It's just a pretty solid looking illusion for the time being! But in terms of what you're doing as an architect you must understand the illusoriness of it because you can make a room appear larger or smaller depending on the light and so on. In fact to make a big space 'read' you have to constrain it. A huge building like St. Peter's in Rome, for example, looks quite small when you're in there, but it's only when you see someone against the base of the columns that you realise it's absolutely vast. And then you take some very small church which would go into the aisle of St. Peter's. It's seems like a very beautiful big space, but it's actually quite small. It's just the illusion that's being created by the structure. And so art, which is really just marks of things on stone, or wood, or canvas is all illusion and symbol. Analytically speaking, a painting of the Buddha is an illusion on a piece of paper or canvas. |